Chasing Joy

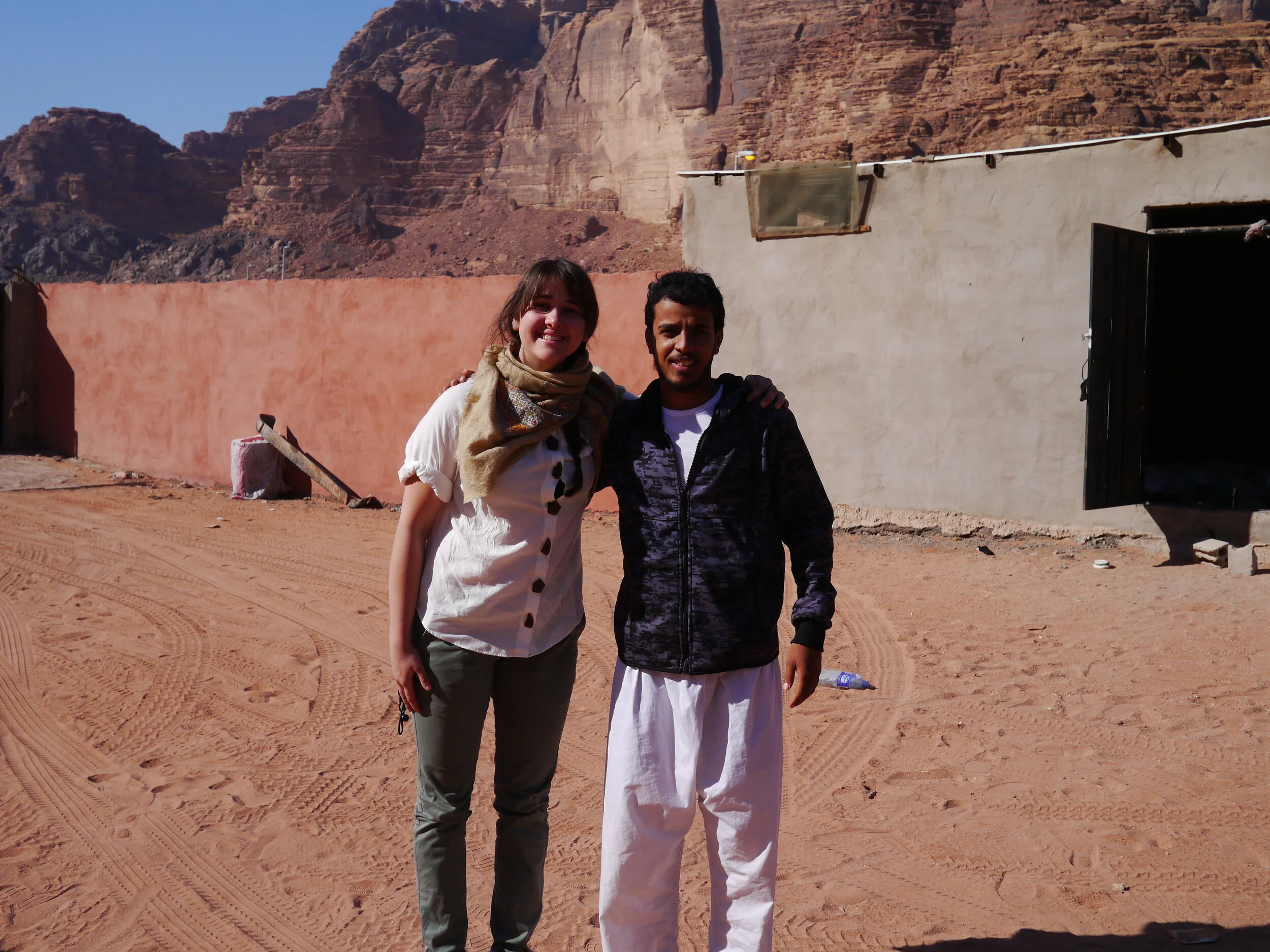

Above: My friend, Jorge. Planter of seeds and a sower of joy.

Chasing Joy

by Belle TukinChasing Joy was written for the purpose of contributing to a collection of stories titled “More than it hurts: and other stories of (mis)adventure by womxn who climb and mountaineer” edited by Wendy Bruere & Emily Small. This was a community project for a local not for profit that connects women in the outdoors. You can find the book here for purchase.

This page is for the sole purpose of sharing the piece with family and friends who do not have access to the book or whom need digital assistance.

I wish to acknowledge the traditional custodians of all the lands of which this piece speaks. Immense love, care and relationship has been sown in the soils long before I or we are here. I am in a process of learning to honour your people, your land, your traditions and wish to see a transformation where deep connection and relationship is restored.

____

4.30am. Coffee on the stove. A few hours sleep. I had found it difficult to get to bed the prior night, I had been nervous and uneasy about the climb we were planning to do the next day. I had taken some valerian, some hops, rubbed some lavender on my temples… I had combined all the magic potions that promised to put my woes to rest but without much success. I think I sensed deep down that something was running dry inside of me - my energy juices, my mental sharpness. Day in, day out, I was pushing my limits both mentally and physically and I wasn’t wise enough to accept rest as an equally honourable component.

I greeted Jorge half asleep in the dim kitchen downstairs, he slid a coffee across the bench to me.

“Belle, I know you aren’t going to like this but we aren’t going to do the climb today,” he said.

“What?!”

“Lisa called Joe last night and we spoke about it. They convinced me that we should wait a little before we try it - there’s no reception, the crux pitch is dangerous, the navigation is tricky... There’s no hurry anyway.”

I looked down at the patterns swirling in my coffee, disappointed that I had lost all that sleep for nothing and we weren’t going to do the project I had fixated on for the last couple of months. Though, in the wee hours of that morning, my swirling coffee would have noticed the equal sense of relief in my eyes as I looked down upon it. I stayed silent for a moment, I was disappointed but I didn’t want to admit I was tired and relieved.

Jorge proposed a plan B, a climb called “Joy”. Clean, unadulterated fun - the kind of climb that doesn’t make you question why you’re doing what you’re doing. We drove out to Kananaskis as the sun rose and arrived at the car park, full of excitement. Although, perhaps a little too jittery with excitement as Jorge’s fingers triggered a bear spray test and we were soon on the floor weeping and coughing at the whiff of the pepper spray designed to subdue bears. We recovered and embarked on a meandering walk through the forest to the base of the climb. Emerging from the forest, we turned a corner to find ourselves at the foot of a 610m grey corner slab. It was a sight to behold, aesthetic beyond measure. Think of a brochure a travel agent would use to try to sell you the Rocky Mountains of Canada - snow capped peaks shooting up from the azure blue lake, pine forests lining the shores and a perfectly inviting gentle slab that seemed to take you right where you would want to be. It was my idea of a stairway to heaven. We enjoyed the brochure-standard view the whole day as we simul-climbed the slab and ran out 70m pitches. It was a day that awoke the senses - you feel the wind wash through your hair, the taste of rope between your teeth, fingers choose camelots and you share a sense of beauty with someone you’re tied to by rope.

My soul sang that day and I was exactly where I needed to be.

I often have dreams of this period in my life where I revisit the mountains that have awakened my senses in one way or another. I fly around Mt Louis and follow the Gmoser Route to the summit, I trace the sandstone walls of Wadi Rum and brush the torrent of water pouring from Takakaw Falls we once climbed beside. Sometimes I visit friends atop Aoraki (Mt Cook) or visit them by an Indian Creek campfire. I’ve even had dreams of Arapiles under snow, with the city pilgrims making the trip to ice climb and ascend mixed routes that the bluff wouldn't usually offer. That day on Joy felt much like that - living out a lucid, flying dream.

I didn’t know it at the time but that day would come to shape the way I saw the world. I had woken up that day, stressed, concerned with the lack of sleep and the monster project we had mapped out many times. Yet choosing not to climb our project that day planted a seed in my mind of what it meant to seek joy over achievement or limits. For us, Joy wasn’t especially hard or technical, yet it was truly an extraordinary part of the world. It was a place with so much wonder and beauty that the woes of performance soon seemed foolish.

Over the years, while I criticised those who were fixated on chasing grades, placing all their identity in the numbers they could clip and the likes on social media they could attain to validate their accomplishments, I had developed my own unhealthy value systems. I had grown to measure my worth in similar ways, needing to keep pushing myself and my limits. I had forgotten how to listen to my breath, my body and equally value rest and stillness.

I had not been taught to climb by people who chased grades or glory, in fact I was always taught by my friend, mentor and boss, Pete, to drink coffee, eat a good breaky and go with someone you enjoy spending time with.

Joy reminded me of this simplicity - that we are making our way up a piece of rock with a friend. Nothing more, nothing less.

Topping out of Joy

Above: Slabs of Joy

Right: One site of my flying dreams - Takakaw Falls route with Jorge.

It was about 6 months after climbing Joy, at the end of 2017, when I lost many of my abilities. I had noticed in the months prior that I started to feel run down, having flu-like symptoms most weeks but pushing on with full-time studies, work, socialising, climbing and running.

In the immediate weeks prior to falling unwell, I noticed I was no longer responding to adrenaline in the same way that I used to, it was as if I was not “waking up” on the wall. I started drinking intense pre-workouts on the way in to, or on, a climb to artificially stimulate my system and pump myself with caffeine to counteract this sensation. I prioritised a sense of urgency as I prepared for a big wall in Oman and felt guilty if I wasn’t actively doing something to prepare for the trip.

I had in fact begun noticing early symptoms many months beforehand. I recall one of my favourite days, climbing the 300m classic, Red Supergiant in Bungonia Gorge, NSW. This climb fitted all my desired criteria at the time despite its questionable rock quality: a route over 200m, more than one star on theCrag.com and low probabilities of running into other parties. I have since acquired higher standards for rock quality but at the time I was missing the long crumbling Yamnuska walls and this was the closest I could come to it, choss included.

My climbing partner Alastair, reflected on the day in his writings and personified this route as some other-worldly-cosmic-supergiant that defends its glory by exploding as you ascend closer to its supernova core. Truly, it was an other-worldly adventure, complete with vertical soil gardens, exploding limestone, Australian tufas, carrot ladders that protrude 15cm out of the rock and bend under body weight. One of the hardest parts of the day though, was finding the first pitch. We searched long and hard for the ‘chipped square’ which was supposed to mark the start but given the meteors of chossy limestone that come flying off this route, a ‘chipped square’ may not be the most distinguishing feature to look for in the gorge. We eventually fluked the start and laughed our weaving way up the face that day. I have treasured and revisited the memory ever since.

Yet, at the top of the 8th pitch, I looked down at the pile of double ropes that had found themselves in a complete noodle soup, tangled and twisted. I remember staring at it for 60 or so seconds, unable to compute what I was looking at. I have untangled many ropes in my time and I could hear a voice speaking gently to me in my head, “Come on Belle, it’s okay, just pick it up and start somewhere”.

I continued to stare, I wasn’t trying to solve the puzzle through a secret vision superpower, I was experiencing some sort of brain-body error, something had seemingly stopped working. I couldn’t move my arms even though they weren’t tired and despite my internal voice gently encouraging me, telling me it was okay. I could feel Al trying to pull the ropes but he was out of sight and we couldn’t hear each other, leaving me unable to communicate the conundrum I was facing. I felt tears rolling down my face and I spoke to myself alternating between, “What’s happening?” and “You’re okay Belle, it’s okay”.

I topped out that day, and I felt a great ecstasy and joy as I shared the sacred supergiant journey with someone I loved but from that day forward, I felt something wasn’t quite right.

Left: Red Supergiant, Bungonia Gorge, NSW. Photo by Alastair McDowell.

Above: Al and I covered in a layer of soil and sandstone as we topped out.

A couple of months after Red Supergiant, I found myself at the doctor’s surgery. I was told that a nasty virus had taken over my body. The doctor, also with a background in Chinese medicine, asked if he could check my Qi point on my toe. Using an instrument that offered a metronome-type sound when reading reference points on your body, he came to my Qi point and, rather shocked, he remarked "Oh dear… you’ve got nothing left in you do you? It shouldn't sound like a flat line."

Blinded by my vision for Oman and expectations of the trip as a defining moment in my climbing journey, I responded, "I'll be ok to get on the plane on Tuesday though if I rest up this weekend?"

My doctor solemnly looked at me with what I felt was a hint of anger, "You have to take this seriously. I'm really sorry, but you might be better this time next year."

I defended my question for a moment before breaking down in tears.

Viruses usually come and go in a few weeks, you feel a little tired and you eventually get over it. For me, this wasn’t the case. I had ‘complications’ to say the least. I sense that I owe this in part to running my adrenal system into the ground for years beforehand. I had gotten a job shovelling horse poo that paid $2.50/hour when I was 11 years old and I haven't stopped since, competing in sports throughout my childhood and teen years, recovering from horse riding accidents, fracturing vertebrate along the way, working multiple jobs while studying full time, climbing trips, mountaineering trips, long distance this that, working here there… it never ended and I had never actually stopped.

We are conditioned to believe this is an achievement but I beg you not to buy it. What I needed was to be conditioned to respect my body and not feel guilt when I honoured it with rest and restoration. I hold hope that we begin to encourage one another to believe that achievements and output are not the defining characteristics of ourselves and others, as climbers or otherwise, but rather we learn to place value on the things that remain invisible - stillness of mind, deep and profound human connection, building communities that seek to do things differently, connectedness with nature, self compassion, balance in all things. These are just some of the life giving, often unseen, elements.

Weeks later, when I had expected to be on the side of Jebel Misht with close friend Az, I instead found myself in hospital, finding it difficult to breathe, in severe pain, skin yellow, incapable of staying awake for more than an hour or two at a time. Eventually they sent me home with steroids to ease some of the inflammation in my body and I seemed to improve slightly. Though, for many months I could not function - they simply labelled this "post-viral fatigue". I lost my ability to think and concentrate. Reading was extremely difficult for my brain and at times staring at a wall was no hard task, it was simply all my body could cope with. Light and noise was excruciatingly painful, I often had to retreat to darkness. Often times, I found it difficult to converse as it was challenging to connect words to my mouth or produce thought. My voice turned monotone as it became too exhausting to express emotively. My physical capacity was heavily impacted, and I would sleep for up to 16 hours a day, and the most mundane of activities became overwhelming difficult. I would regularly take cold showers as my body felt as if it were permanently burning. While these showers would blast cold water, I had to sit in my shower to bathe as standing felt increasingly impossible, and washing my hair was such a significant exercise that I would save it for my 'good days' and need rest after doing so.

I felt my illness stripped me of the physical ability to interact with the world despite deep desires, a strong drive and many plans to return to the arenas I once thrived in. At the same time 'feeling exhausted' wasn't remarkable enough for a lot of people to understand the reality I lived day-to-day. It was difficult for people to ‘see’ a system ceasing to function inside a young woman in her early 20s. Those intimate moments of blasting cold water on my burning body as I sat down in the shower to wash my hair were not visible to the world around me. For a long time, I wished I had been in a car accident. I didn’t want to end my life or hurt myself nor was I experiencing depression - I only wished that my illness could be made visible. I thought that somehow if my disabling experience was visible, it would legitimise it.

Throughout the year following becoming ill, I would have moments of feeling awake and well, and I would race out to the mountains and use up any juice in the system. I would go out to Cosmic County, find myself busting to aid climb up Dog Face, drive down to Point Perpendicular, or rush out to Narrowneck. But this always came at a high physical cost. At times I would pass out or fall asleep in the bush, and would spend weeks recovering, often bound to bed between short days at work until the next sporadic good day. The glorious day aiding up Dog Face Wall took me about six weeks to recover from. Admittedly, it is a memory I laugh at and treasure to this day. The day was an adventure in many ways, with hikers calling the police, police rescue team visiting and then spectating, falls and micro cams ripping down to the belay.

Though, spending six weeks bed-bound begged the question of whether I was repeating the cycles that may have contributed to the state I found myself in. Was I adapting or resisting? Was I simply reinforcing unhealthy values that would prevent recovery, whatever that meant or may look like?

It was a year post-illness that I found myself back in Wadi Rum in Jordan visiting my Bedouin brother, Atallah and accompanying some dear friends up routes as I desperately clung to my vision of recovery. Although this was a gentle and cautious trip, soon after my return, and for various unrelated reasons, I relapsed. This time, worse. For many months I had barely any days of feeling conscious, and I spent most of the summer only able to make it downstairs late in the morning to make some coffee and feed the chooks. I would lie out in the yard and drift in and out of sleep. I began reading poetry as books were no longer within my capabilities. This relapse had spurred me to move out of Sydney and to the Blue Mountains almost overnight. It had been a familiar second home since I was a teenager and knowing the debilitating nature of the illness before me and unknowing as to how long the relapse would last, I only knew that I could not bear to stare at the same ceiling in my Sydney apartment, the hullabaloo of the highway hum ringing in my ears. The noise alone drove me insane and the inability to access nature from where I was - no sea, no bush, no trails in sight - left me feeling suffocated, not just by the city pollution.

Wadi Rum

Home of my Bedouin brother, Atallah.

2018 marked the first year of my recovery and was characterised by these “pushes” and “pulls”. It seemed a race toward an idea of recovery and the sense that I had to fight to be well, that I had to earn my way back to health and fitness, and that I had to push myself to see improvement. It took me a long time to realise this isn’t always the answer.

It had been around 18 months of illness when I distinctly remember one last "push" toward recovery that came at the end of the summer of 2019. I had been in the mountains a few months and I was experiencing a few good days here and there. I decided to take myself for a run to test out my capacity. I ran from Scenic World to the Three Sisters and dropped down 998 stairs, to Leura forest via Dardanelles Pass, continuing along Federal Pass for a while before climbing the near-1000 steps back to the plateau. It was around a 10km loop. Given this was a regular run in a previous time, I thought it was reasonable. It was hard to reconcile what my mind believed I was capable of and what my body was telling me it was capable of. This time I found myself walking most of the way home and seemingly drifting in and out of lucidness. It was alarming to wake on my back porch some hours later, the sky suddenly night, the temperature much cooler and still dressed in my running gear. I was unable remember falling asleep or passing out. It took me about two months to regain the ability to freely walk the 20-minute bush loop by my house.

We can exist in communities and environments that put value on mental strength, that if you are strong in mind, you can achieve anything. Seemingly, I understood that to mean that as an athlete of any level, mental grit was bound to reward me in physical performance. This had proven true much of my life and so it came as a confronting curb to not be rewarded for my continual physical perseverance as I believed it to be the answer for my recovery.

The run to Leura Forest was the last time I recall carrying a strong "push yourself" mentality. I had hoped that by consistently pushing my physical capacities, I would eventually return to climbing and foster my physical recovery. I feel a young Mark Twight would read this as the point at which I gave up, the point which separates the mountaineer from the alpinist. Ironically, over the years I’ve come to accept that alpinism isn't for me. That doesn't make alpinism wrong and that acceptance doesn't make me ordinary. In the same sense, I can't say I ever gave up or I became weaker the moment I decided to no longer “push myself”, I simply woke up to my body's call - it told me, ”No more, not yet”. And it had taken me 18 months to respond simply with “okay”.

I am deeply grateful that in this period of saying “okay” to my body’s call that I had a circle of brave, persistent and loving people around me who reminded me that our bonds ran deeper than the physical expressions we may once have shared. This was community, this was communion, this in itself was a joy - to learn what it meant to be human to human again and to begin seeing new possibilities. They were willing to sit in the silence, witness the mess, weather the storm and learn with me what it meant to explore and find joy in a new season.

A year post-infection finding solace on the shores of Tasmania during the period of relapse

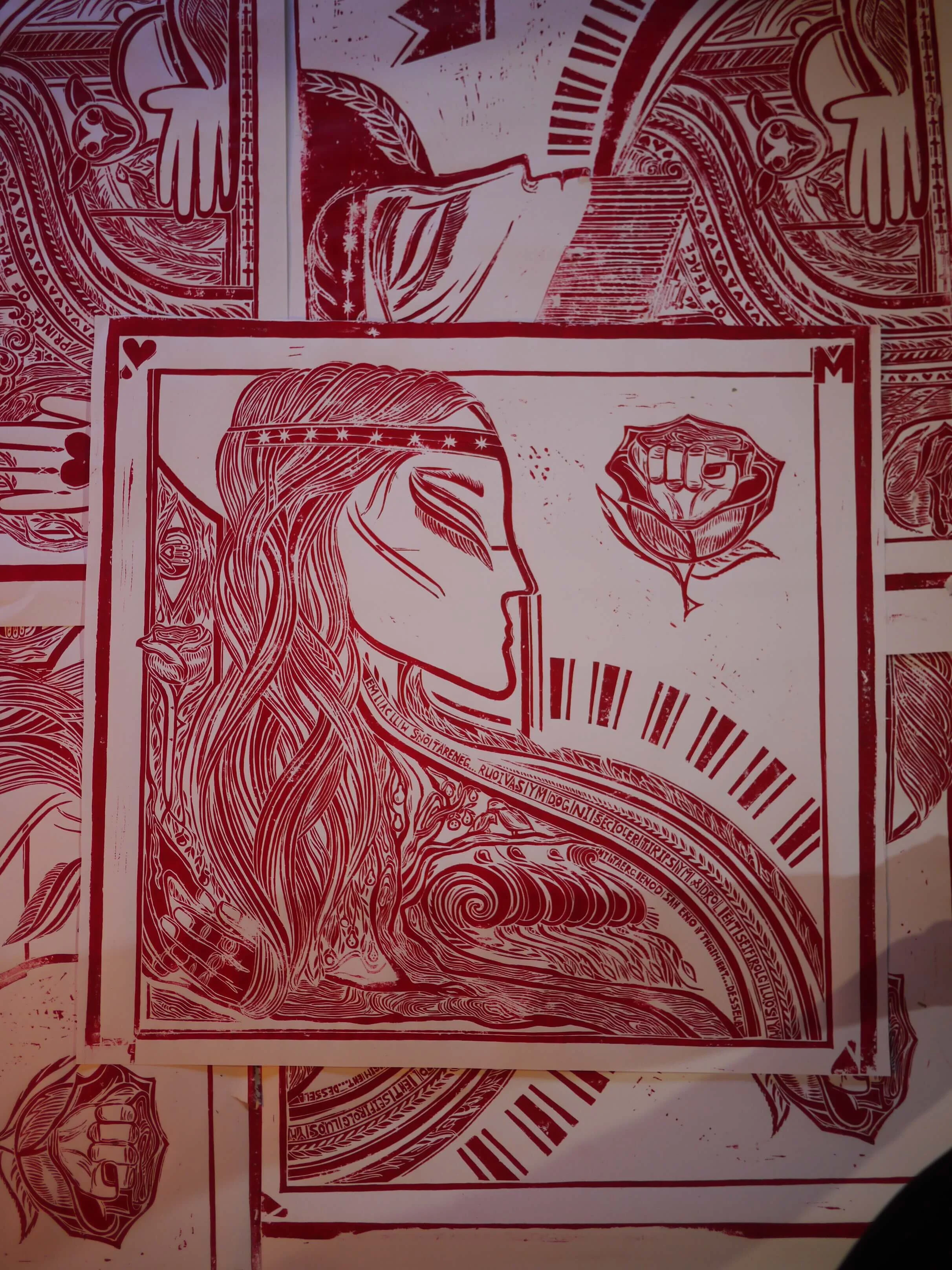

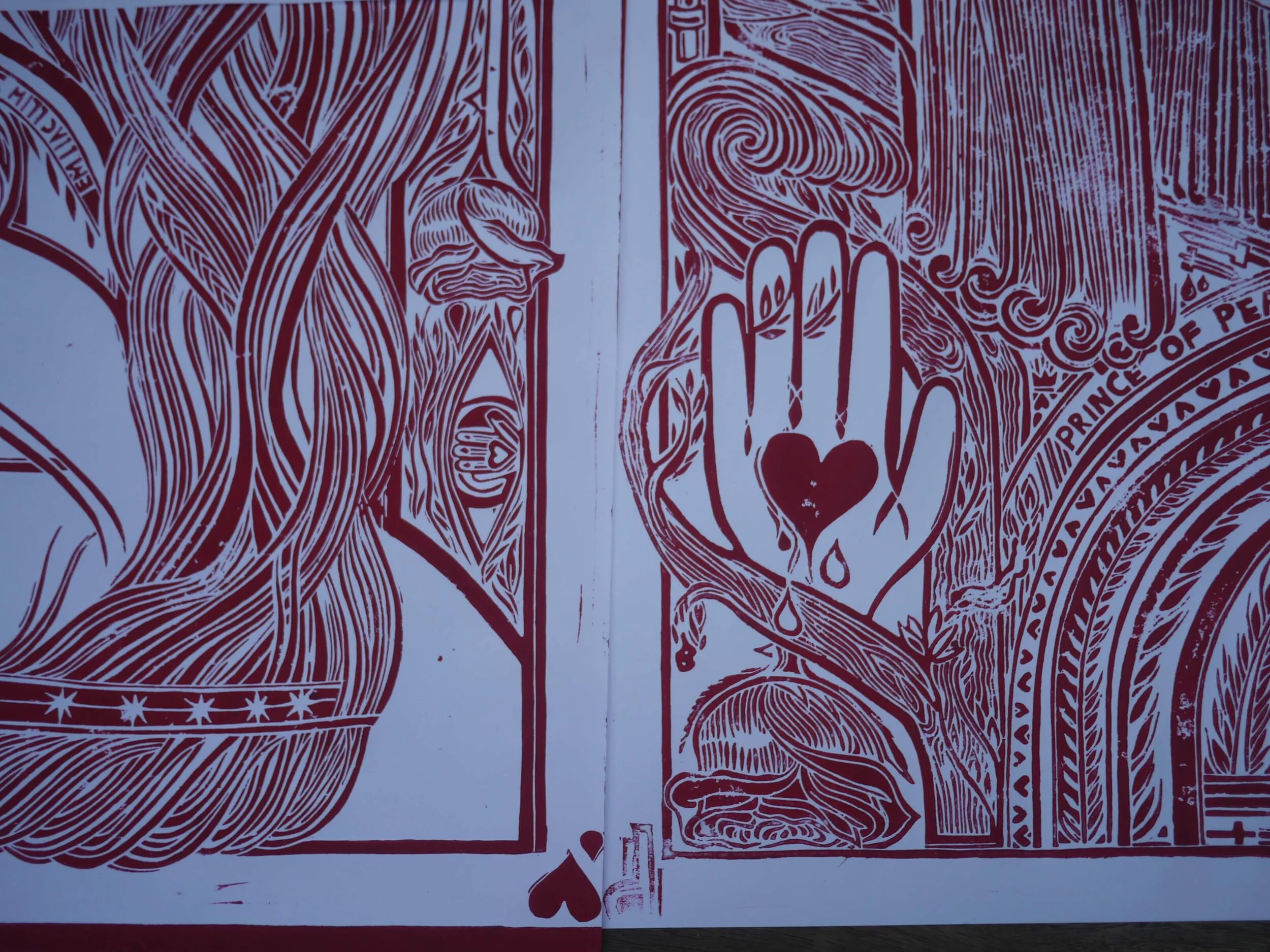

It started to look different after that run to Leura Forest - it had to look different for me to survive and eventually flourish. Change came in the form of some lino, two monks and 2 x 2.4m canvases that I bought off Gumtree. And so a new season came into blossom, an exploration of colour, texture and silence rather than grit, distance and adrenaline.

I embarked on a lino pilgrimage in my dining room, carving portraits under a light bulb into the wee hours. Lino is a short word for “linoleum printing”, which takes the concept of ancient Japanese woodblock printing techniques and applies them to a more readily available and softer material - linoleum. Yes, the plastic sheeting that may still line your grandma’s kitchen floor. Admittedly, it currently lines my bathroom floor in faux black and white tiles. I invested in a set of fancy, swiss-made, wood carving tools and began carving blocks of lino with intricate stories of people - reimagining their identities visually. I can’t recall how or why I decided to go to the art shop one day and buy some lino but nevertheless I had found myself in a rather niche corner of the world.

It completely consumed me, and a 12 hour-day of carving dipping in and out of this world was not an unusual occurrence, with naps and tea between. I joined “linocut friends”, a community group on Facebook, where I would ask these welcoming strangers for advice on all the technical difficulties I was experiencing as a beginner. Soon I was excited to get out of bed, brew some coffee, sit down and get to work on the latest portrait without any pressure of performance. It was a new experience to be excited by something so sedentary and still. Pieces of lino would follow me everywhere, including work at the Ledge Climbing Centre where in the zombie hour before closing (9pm - 10pm), I would gently carve one of my projects. The Ledge community encouraged and followed me down this odd rabbit hole with many people sitting with me for a cup of tea, asking lots of questions as I continued on carving.

While lino was my preferred exploration, I became curious about other art forms that could excite me in ways carving was able to. Paint seemed an obvious choice - messy, expressive and colourful. The answer was to search Gumtree for ‘large canvas’ which returned a surprising hit - a lady selling some 2.4m x 1.8m blank, stretched canvases. I couldn’t believe my eyes and like a shopper falling for the consumerism of sale season, I impulse purchased both of them. I called on my longtime friend, mentor and boss from the Ledge, Pete to help with this logistical nightmare (given I have a 3 door Kia Rio) who strapped them onto the back of his motorbike trailer and we got them up the hill to the Blue Mountains. I slowly started painting the panels between carving sessions as a way to encourage gentle movement of my body as I stood, sat and stretched to reach each corner. It took a few months and many naps to cover one with a sea of blue ... as well as covering half my wardrobe with the same hue.

During this season, a third ritual was born. When dusk would set upon my painting days, my landlord would invite me to sit with two monks in the forest each evening. In a small vihara nestled on the outskirts of the Blue Mountain’snrainforest, a few monks practiced stillness of mind and body. They opened their sanctuary twice a day, morning and evening, and allowed laypersons to share in an hour of silent meditation. While Buddhism isn't my faith-practice, I found that in the hours I spent sitting with the gracious monks, observing in silence, listening to the calls of the black cockatoos, or the rain hitting the tin roof, I was invited to challenge the old push-toward-recovery that still smoldered somewhere quietly within me. The spirit of silence, common to us all, encouraged me to continue embracing stillness and make peace with the state of my body and system.

Ironically, the silence of an hour can sometimes feel like standing at the foot of a headwall - intimidating, overwhelming and wondrous all the same. Yet, when you break a mountain down into bite-sized pitches, you eventually find a feasible way to reach the summit, just as each minute leads to an hour in a meditation. Of course, each minute can sometimes feel painfully slow and the seconds seem to freeze. While on other occasions, I can experience an otherworldly floating sensation, where feelings of serenity, gratitude and contentment bubble to the surface. It was in the gooey-uprisings that it became abundantly clear that my soul was still singing and I was exactly where I needed to be.

Moonlight Conversations

One of the 2.4m canvases. It is covered in stories of people, of dreams, of poetry, of psalms, of conversation.

Above: Lino prints

Below: Painting by night

Over the years, I had forged a sense of self in the depths of these mountains, in the cold canyons and in the wilds of the Wolgan. Part of it was a sense of being grounded in the rhythms of nature, but it was also inextricably linked to the physical ability to scale rocky landscapes and traverse skylines. Unknowingly I had focused on the mountains as a playground, and forgotten how to experience it as a sanctuary of stillness and silence.

When I moved to the Mountains at the eclipse of my relapse, I knew deep down that moving to the Mountains would also ask me to confront the memories of the past that no longer felt a reality: the dreams and friendships I felt slipping away that often centered on physicality, on moving through a landscape in a way that was no longer within reach. I intensely grieved for many months, I grieved my loss of physical abilities for the second time within a year and I grieved the memories of climbing, running, hiking, and moving that lay in such a sacred place. I grieved a loss of identity that summer. I was coming to realise that while I was still in the same body, I was shedding a skin. While the mountains remained unchanged, my physical capabilities had and my expectations needed to shift, willingly or unwillingly.

If you had chosen to accompany me on even the smallest of walks, you would have found me tracing the patterns of the sandstone, tears rolling down my face, or sitting on a bench crying until there were nothing left to shed. I would often lie on the valley floor (if I could make it) and weep. I seemed to emerge lighter after each visit, feeling cleansed. The trees have a way of wrapping their arms around you, and I have come to appreciate the term shinrin-yoku. This is a Japanese word that translates to ‘forest-bath’ which is a practice of immersing one’s senses in the forest atmosphere. It was during this season of re-birthing and forest-bathing that my senses felt suddenly heightened and I began to soak in a new relationship with the land on which I was a guest. I would notice the sound of the wind, the sun on my skin, the smell of the grass, and I realised I had the patience to watch clouds drift past as I lay beneath them. I had a deep appreciation that I was living out my illness in the quiet of the mountains, I was gladly sharing my tears with the forest floor and I found myself laughing and crying and talking to the trees. It was an odd contrast. Maybe I lost my mind, but whatever was happening I began to feel the joy I once found on the wall - only it was a new joy triggered by the smallest of ordinary occurrences.

I reflect now in the ways that I understood climbing to be a curious exploration of sorts, a way to explore limits, express myself, be playful but also an avenue through which to explore inward. Yet I have come to understand it as something much more and much less - its movement, its human connection and a gift to those who are able to receive it. The essence then, of climbing, does not have to be confined to physical expression. Perhaps the same seeds that spur us to walk onward and climb upward, can manifest in many ways. I have come to realise that when I sit in silence in the forest, alone or in the company of monks, I can encounter a sense of connectedness and peace, something I once felt atop of Joy. Carving lino under a desk lamp in the middle of the night has induced much the same concentration and all-consuming flow state that only the most engaging of rock climbs have enabled me to feel. A slow evening walk along Narrowneck Plateau, looking out to Dog Face Wall illuminated under the waning dusk light, brings much the same contentment and reflection as a quiet solitary moment on the wall as you wait patiently for your partner.

In truth, I couldn’t have been told this nor believed it early on - that other activities, even the most mundane, still and ordinary, could bring about the same human experiences that climbing, running and walking have offered me. Early in my recovery, I was either bombarded with a shallow positivity from others - ‘It’s all in your mindset’, ‘You’ll get back’, ‘you won’t lose that much muscle’, or the more common, ‘It’ll pass’ to the invalidating, ‘have you tried anti-depressants’. I didn’t like any of these even if well intentioned. Instead, if I could offer an alternative to myself of years ago and to those currently ‘not able’, it is something much more simple.

Your soul will sing again.

Perhaps your soul will sing a new song, perhaps not in the time frame you had hoped, perhaps not in ways you can imagine, but the essence of what you love will return to you again, on or off the wall. You will come into a way of being that makes you feel alive. I deeply hope that we can follow the long wandering rocky routes again but may we remain thankful for the quiet, for rest, for friendship and may we listen and respect the needs of our bodies in the meantime. There’s no hurry.

A poem that spoke peace. May it bring the same to you.

For one who is exhausted, a blessing

By John O’ Donohue

When the rhythm of the heart becomes hectic,

Time takes on the strain until it breaks;

Then all the unattended stress falls in

On the mind like an endless, increasing weight.

The light in the mind becomes dim.

Things you could take in your stride before

Now become laborsome events of will.

Weariness invades your spirit.

Gravity begins falling inside you,

Dragging down every bone.

The tide you never valued has gone out.

And you are marooned on unsure ground.

Something within you has closed down;

And you cannot push yourself back to life.

You have been forced to enter empty time.

The desire that drove you has relinquished.

There is nothing else to do now but rest

And patiently learn to receive the self

You have forsaken in the race of days.

At first your thinking will darken

And sadness take over like listless weather.

The flow of unwept tears will frighten you.

You have traveled too fast over false ground;

Now your soul has come to take you back.

Take refuge in your senses, open up

To all the small miracles you rushed through.

Become inclined to watch the way of rain

When it falls slow and free.

Imitate the habit of twilight,

Taking time to open the well of color

That fostered the brightness of day.

Draw alongside the silence of stone

Until its calmness can claim you.

Be excessively gentle with yourself.

Stay clear of those vexed in spirit.

Learn to linger around someone of ease

Who feels they have all the time in the world.

Gradually, you will return to yourself,

Having learned a new respect for your heart

And the joy that dwells far within slow time.

Thank you.

I wish to say thank you, a lot of thank you-s - not because this is an award ceremony but because I wish to express gratitude in all that I write, and wherever I may walk.

I wish to thank Pete. Thank you for encouraging me, supporting me, listening. To flying, climbing and eventually hiring me. I am grateful to learn every time that it’s about taking time to enjoy the journey. Thank you.

Jorge. You planted seeds of joy and your friendship continues to water these.

Al, thank you for encouraging me to write this piece, your friendship and your tireless effort editing out my grammatical errors.

Thank you to Wendy and Emily for putting this project together which consequently gave me a reason to write and a lockdown activity.

Thank you, Peggy and Mel - our shared walks, hugging trees, love for the bush, our talks, shared meals. Thank you, I am forever grateful.

To Az, your friendship means the world to me. Your non-chalant support, your check ins, your last-minute belays. To Nik, to Alex, you are angels - the ways in which you lighten my life are immeasurable. Iryna, my old lady - may we continue to grow slow and old, full of laughter and sourdough.

To my many families (incl. Tukins, Sherwins, Bridges, Kemps, Lees, Shanes). My life is forever changed by doing life with all of you.

To all my friends, who have held my hand, who have fed, sheltered, cared, bathed, accompanied me with such generosity and kindness. I am indebted.